The history of mountaineering in San Martino di Castrozza is rich in anecdotes, adventures, and emblematic episodes where the determination of the early mountaineers and Mountain Guides allowed them to accomplish epic feats. On this page, you will discover the places touched by their bold conquests, which you will have the opportunity to retrace along the Palaronda itineraries. In fact, in the Pale di San Martino, every step that you take tells a long story of courage and passion for the mountains.

For over a century and a half, San Martino di Castrozza has been a privileged destination for mountain tourism, but its origins date back to a time when the concept of mountaineering did not yet exist. In the past, indeed, the basin where San Martino is located was simply a mountain pasture, with some rural buildings, a church, and a hospice managed by Benedictines, which occasionally offered hospitality to travelers and traders passing between the Val di Fiemme and the Valle di Primiero. This wild and unspoiled place attracted the attention of European explorers only in the second half of the 19th century, during the romantic era of the Grand Tours of Italy. The construction of the first hotel by Leopoldo Ben in 1872, the Albergo Alpino, marked the beginning of an increasingly frequent influx of foreign aristocratic tourists, intellectuals, and artists, as well as geologists and botanists, fascinated by the majesty of the Pale di San Martino and the Dolomites.

San Martino di Castrozza attracted well-known figures such as Princess Sissi, General Conrad, composer Richard Strauss, Viennese writer Arthur Schnitzler—whose novel “Fräulein Else” is set in a hotel in San Martino—and the father of psychoanalysis, Sigmund Freud, all of whom contributed to making this location even more renowned. This first golden age of tourism was interrupted by the outbreak of war on May 24, 1915, after which the Austrians, before leaving the town, set fire to all the buildings, except for the church. After the conflict, San Martino was rebuilt and began to transform into a real town, with shops and private houses, still retaining to this day its fascinating history of mountaineering and tourism.

Who doesn’t know San Martino di Castrozza, doesn’t know the Dolomites – Gunther Langes

In the late nineteenth century, interest in the Alps began to grow among European travelers, who were fascinated by their wild nature and unexplored character. Before this period, the mountains were not considered places of particular interest by the inhabitants of these valleys, and were simply seen as dangerous territories, lacking productive utility, and therefore often didn’t have specific names. With the advent of the mountaineering season, a climate of race to conquer the Alpine and Dolomite peaks emerged, and it is during this period, from the 1860s onwards, that the Pale di San Martino began to attract explorers in search of adventures. The boldest mountaineers aimed to be the first to climb that one mountain or to complete that other traverse, thus initiating a new era of exploration and conquest.

These courageous pioneers were drawn by the wild and mysterious charm of the mountains, embarking on adventures that took them across remote valleys, up vertiginous rock walls, and to conquer the highest peaks. It was they who gave names to the various peaks, tracing the first mountaineering trails and paving the way for successive generations of climbers. In particular, in the Pale di San Martino Massif, these pioneering feats helped shape and give meaning to the mountainous landscape, making it a sought-after destination for mountaineering enthusiasts from around the world. By trekking along the Palaronda trails, you’ll retrace the footsteps of the early mountaineers, immersing yourself in the history and the emotion of their conquests.

The mountaineering exploration of the Pale officially begins with the first traverse of the Pale Plateau, carried out on June 1, 1865, by a group consisting of Freshfield, Tuckett and the two guides Dévouassoud and P. Michel. Starting in San Martino they climbed the Rosetta, then took the Comelle valley and arrived in Gares. Thanks to Freshfield’s travel journal, we can relive that adventurous day. After spending the night at the San Martino hospice, the group set out at 5 in the morning towards the Plateau, taking 3 hours to reach the Passo della Rosetta, and then venturing into the Comelle valley. In search of the pass to reach Gares, they encountered a series of obstacles, including the narrow gorge of the Orrido delle Comelle, where they found pieces of wood wedged in the rock to form a rudimentary staircase, a sign that the locals were familiar with that place. Beyond this passage, the explorers found a farmer mowing grass, and they were impressed by the warm hospitality of this man, who insisted that they follow him to his cabin, where he offered them milk, cheese, and butter.

The rocky landscape around us was of the most splendid grandeur, overhanging cliffs towered above us on the right, and on the left the pillars of Cimon della Pala and Cima Vezzana culminated in stupendous pinnacles.

The Cimon della Pala is an extraordinary mountain, whose most famous and eternal poetic definition was given by John Ball, who baptized it the “Matternhorn of the Dolomites”, for its resemblance to the famous Swiss mountain. A first attempt to conquer its summit was made from the Passo della Rosetta up the Val dei Cantoni by the Austrian Grohmann, who had to stop in front of a vertical wall of about thirty meters. After unsuccessfully attempting the same route as Grohmann, Whitwell had the insight to try from the northern side, ascending the Travignolo Glacier. The English mountaineer completed the feat in 1870 with two of the best guides of that time: Santo Siorpaes from Cortina and Christian Lauener from Lauterbrunnen. Once they ascended the Travignolo Glacier, the climbers faced the steep icy rocks of the northern slope, a dangerous ascent due to frequent rockfalls, and with courage and determination, they finally reached the summit of Cimon della Pala, sealing the conquest of what is perhaps the most emblematic mountain of the Pale.

The enormous pinnacle towered above us, boasting its appearance of absolute inaccessibility and seeming to mock any human attempt to reach the summit.

On September 5, 1872, Douglas Freshfield and Charles Comyns Tucker embarked on the daring feat that would lead them to conquer Cima della Vezzana, the highest peak of the Pale di San Martino. The adventure is described in detail in the Alpine Journal, and despite its relative ease, it had a certain epic character. The two Englishmen were not accompanied by the usual guides Dévouassoud and Santo Siorpaes, so they hired as the third member of their team a chamois hunter who had been recommended to them at the inn in Paneveggio. At the first light of dawn, they set off towards the Travignolo Glacier, which they began to ascend until they encountered the first difficulties: in front of the edge of a crevasse, the hunter refused to continue, judging the terrain too rugged. But the two Englishmen were not discouraged, and they assessed that their experience was sufficient to continue even on their own. Despite a slip in the final part, they succeeded in the undertaking, and upon reaching the summit, they could contemplate the cairn erected by Whitwell on Cimon della Pala two years earlier, and they had the impression that it was slightly higher than them, unaware that what they had ascended was actually the highest peak of the Group.

That which we are moving on is not solid ground, gentlemen. My life is worth more than any money!

One of the earliest written accounts highlighting mountaineers’ interest in the majestic Sass Maòr is found in an article written by Leslie Stephen, father of the famous English writer Virginia Woolf. Presented publicly at the Alpine Club of London on January 25, 1870, the article called “The Peaks of Primiero” paved the way for many future mountaineering feats. Stephen had the intuition that the Sass Maòr could not be conquered from the Val Pradidali, so he suggested an alternative route, through the valley that descended from the Cima di Ball. Mountaineers Tucker and Beachroft treasured this advice, and it was from the upper Val della Vecchia that, on September 4, 1875, accompanied by mountain guides Dalla Santa and Dévouassaud, they reached the pass between Sass Maòr and Cima della Madonna. From there, they lifted their gaze to the peak that only a few hours earlier seemed an unattainable goal, and after 13 1/2 hours they finally reached the summit. The Sass Maòr became even more coveted and famous in 1926, when Emil Solleder and Franz Kummer climbed the massive East Face, opening one of the first grade VI routes, thus adding another chapter to the epic history of this vertical tower.

It’s the sense of desperate distance from the world below that makes the summit of Sass Maor such a tremendous and fascinating pedestal.

The unquestionable beauty of the Pala di San Martino, which embodies in its rocks the shape evoked by the toponym “pala”, with its elegant lines rising skyward, has made it one of the most coveted peaks by mountaineers for years. Indeed, all the pioneers of the Pale had at least once desired to conquer this sublime tower. However, it wasn’t until July 13, 1878, when the Viennese climbers Julius Meurer and Alfredo Pallavacini, after an entire week of attempts, finally managed to complete the decisive assault on the summit. They were accompanied by the guides Santo Siorpaes, Arcangelo Dimai, and by the all-rounder of the hotel where they were staying, a character destined to soon become the first of the great Alpine Guides of San Martino and one of the most famous in the Dolomites: the young Michele Bettega. On July 24, 1920, the inauguration of what would become the most famous route to the Pala di San Martino took place: the Grand Pillar. This route, opened by Gunther Langes and Erwin Merlet, remains to this day one of the most beloved in the Pale di San Martino Group.

Intrigued, we looked at the beautiful summit book. We were the first roped party on the summit after the war. Carefully sharpened, the pencil had waited six years for the next recording, careless of the upheavals the world had experienced.

Even Cima Canali, whose beauty is encapsulated by the Bavarian Gustav Euringer’s description as a tall and slender Gothic cathedral, lost its status as a virgin peak when it was conquered by the well-known Tucker and Michele Bettega on August 30, 1879. The route followed by the first climbers follows the evident rift that diagonally divides the side of the mountain facing the Pradidali Hut, then crosses over to the other side to reach the summit. It’s also worth mentioning the opening of what is now the most famous route on the west face of Cima Canali, the renowned Buhl-Erwing Route, inaugurated by the two climbers on the cool morning of September 9, 1950. Even today, this route attracts mountaineers from all over Europe.

Those who gaze upon its terrifying sheer walls believe it to be inaccessible.

The mountaineering exploration of the Pale officially begins with the first traverse of the Pale Plateau, carried out on June 1, 1865, by a group consisting of Freshfield, Tuckett and the two guides Dévouassoud and P. Michel. Starting in San Martino they climbed the Rosetta, then took the Comelle valley and arrived in Gares. Thanks to Freshfield’s travel journal, we can relive that adventurous day. After spending the night at the San Martino hospice, the group set out at 5 in the morning towards the Plateau, taking 3 hours to reach the Passo della Rosetta, and then venturing into the Comelle valley. In search of the pass to reach Gares, they encountered a series of obstacles, including the narrow gorge of the Orrido delle Comelle, where they found pieces of wood wedged in the rock to form a rudimentary staircase, a sign that the locals were familiar with that place. Beyond this passage, the explorers found a farmer mowing grass, and they were impressed by the warm hospitality of this man, who insisted that they follow him to his cabin, where he offered them milk, cheese, and butter.

The rocky landscape around us was of the most splendid grandeur, overhanging cliffs towered above us on the right, and on the left the pillars of Cimon della Pala and Cima Vezzana culminated in stupendous pinnacles.

The Cimon della Pala is an extraordinary mountain, whose most famous and eternal poetic definition was given by John Ball, who baptized it the “Matternhorn of the Dolomites”, for its resemblance to the famous Swiss mountain. A first attempt to conquer its summit was made from the Passo della Rosetta up the Val dei Cantoni by the Austrian Grohmann, who had to stop in front of a vertical wall of about thirty meters. After unsuccessfully attempting the same route as Grohmann, Whitwell had the insight to try from the northern side, ascending the Travignolo Glacier. The English mountaineer completed the feat in 1870 with two of the best guides of that time: Santo Siorpaes from Cortina and Christian Lauener from Lauterbrunnen. Once they ascended the Travignolo Glacier, the climbers faced the steep icy rocks of the northern slope, a dangerous ascent due to frequent rockfalls, and with courage and determination, they finally reached the summit of Cimon della Pala, sealing the conquest of what is perhaps the most emblematic mountain of the Pale.

The enormous pinnacle towered above us, boasting its appearance of absolute inaccessibility and seeming to mock any human attempt to reach the summit.

On September 5, 1872, Douglas Freshfield and Charles Comyns Tucker embarked on the daring feat that would lead them to conquer Cima della Vezzana, the highest peak of the Pale di San Martino. The adventure is described in detail in the Alpine Journal, and despite its relative ease, it had a certain epic character. The two Englishmen were not accompanied by the usual guides Dévouassoud and Santo Siorpaes, so they hired as the third member of their team a chamois hunter who had been recommended to them at the inn in Paneveggio. At the first light of dawn, they set off towards the Travignolo Glacier, which they began to ascend until they encountered the first difficulties: in front of the edge of a crevasse, the hunter refused to continue, judging the terrain too rugged. But the two Englishmen were not discouraged, and they assessed that their experience was sufficient to continue even on their own. Despite a slip in the final part, they succeeded in the undertaking, and upon reaching the summit, they could contemplate the cairn erected by Whitwell on Cimon della Pala two years earlier, and they had the impression that it was slightly higher than them, unaware that what they had ascended was actually the highest peak of the Group.

That which we are moving on is not solid ground, gentlemen. My life is worth more than any money!

One of the earliest written accounts highlighting mountaineers’ interest in the majestic Sass Maòr is found in an article written by Leslie Stephen, father of the famous English writer Virginia Woolf. Presented publicly at the Alpine Club of London on January 25, 1870, the article called “The Peaks of Primiero” paved the way for many future mountaineering feats. Stephen had the intuition that the Sass Maòr could not be conquered from the Val Pradidali, so he suggested an alternative route, through the valley that descended from the Cima di Ball. Mountaineers Tucker and Beachroft treasured this advice, and it was from the upper Val della Vecchia that, on September 4, 1875, accompanied by mountain guides Dalla Santa and Dévouassaud, they reached the pass between Sass Maòr and Cima della Madonna. From there, they lifted their gaze to the peak that only a few hours earlier seemed an unattainable goal, and after 13 1/2 hours they finally reached the summit. The Sass Maòr became even more coveted and famous in 1926, when Emil Solleder and Franz Kummer climbed the massive East Face, opening one of the first grade VI routes, thus adding another chapter to the epic history of this vertical tower.

It’s the sense of desperate distance from the world below that makes the summit of Sass Maor such a tremendous and fascinating pedestal.

The unquestionable beauty of the Pala di San Martino, which embodies in its rocks the shape evoked by the toponym “pala”, with its elegant lines rising skyward, has made it one of the most coveted peaks by mountaineers for years. Indeed, all the pioneers of the Pale had at least once desired to conquer this sublime tower. However, it wasn’t until July 13, 1878, when the Viennese climbers Julius Meurer and Alfredo Pallavacini, after an entire week of attempts, finally managed to complete the decisive assault on the summit. They were accompanied by the guides Santo Siorpaes, Arcangelo Dimai, and by the all-rounder of the hotel where they were staying, a character destined to soon become the first of the great Alpine Guides of San Martino and one of the most famous in the Dolomites: the young Michele Bettega. On July 24, 1920, the inauguration of what would become the most famous route to the Pala di San Martino took place: the Grand Pillar. This route, opened by Gunther Langes and Erwin Merlet, remains to this day one of the most beloved in the Pale di San Martino Group.

Intrigued, we looked at the beautiful summit book. We were the first roped party on the summit after the war. Carefully sharpened, the pencil had waited six years for the next recording, careless of the upheavals the world had experienced.

Even Cima Canali, whose beauty is encapsulated by the Bavarian Gustav Euringer’s description as a tall and slender Gothic cathedral, lost its status as a virgin peak when it was conquered by the well-known Tucker and Michele Bettega on August 30, 1879. The route followed by the first climbers follows the evident rift that diagonally divides the side of the mountain facing the Pradidali Hut, then crosses over to the other side to reach the summit. It’s also worth mentioning the opening of what is now the most famous route on the west face of Cima Canali, the renowned Buhl-Erwing Route, inaugurated by the two climbers on the cool morning of September 9, 1950. Even today, this route attracts mountaineers from all over Europe.

Those who gaze upon its terrifying sheer walls believe it to be inaccessible.

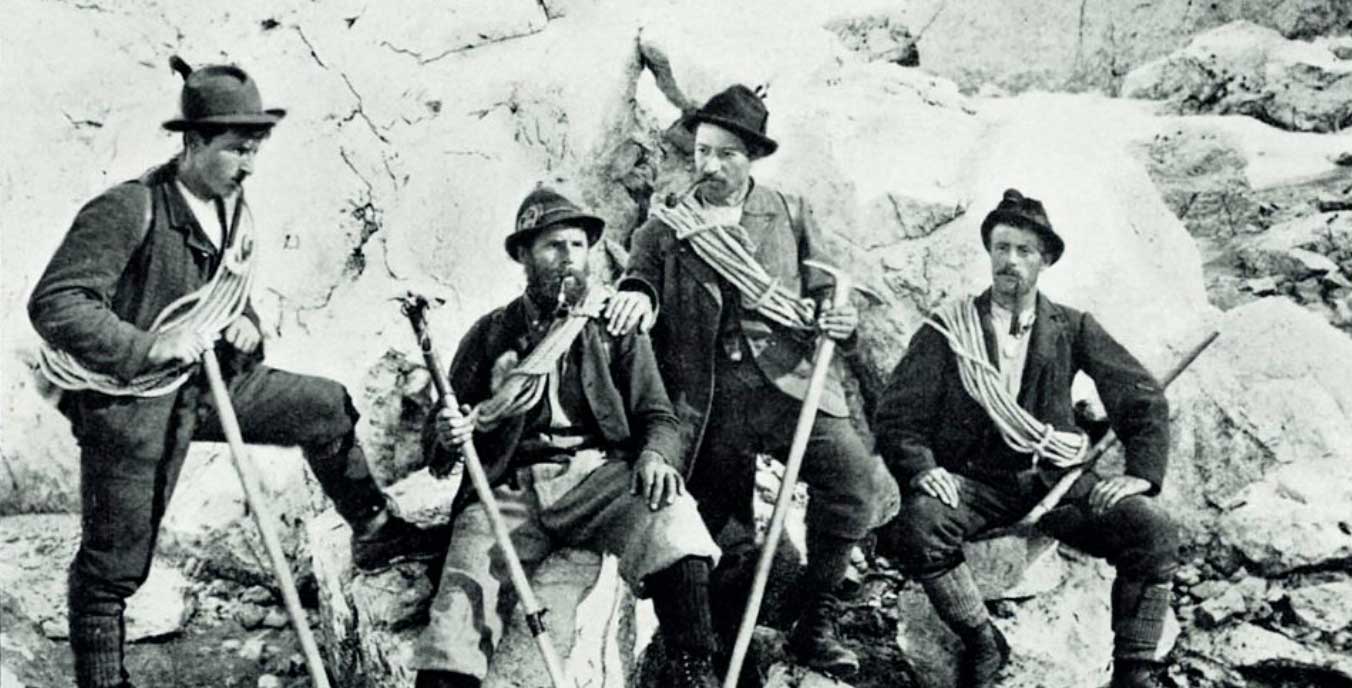

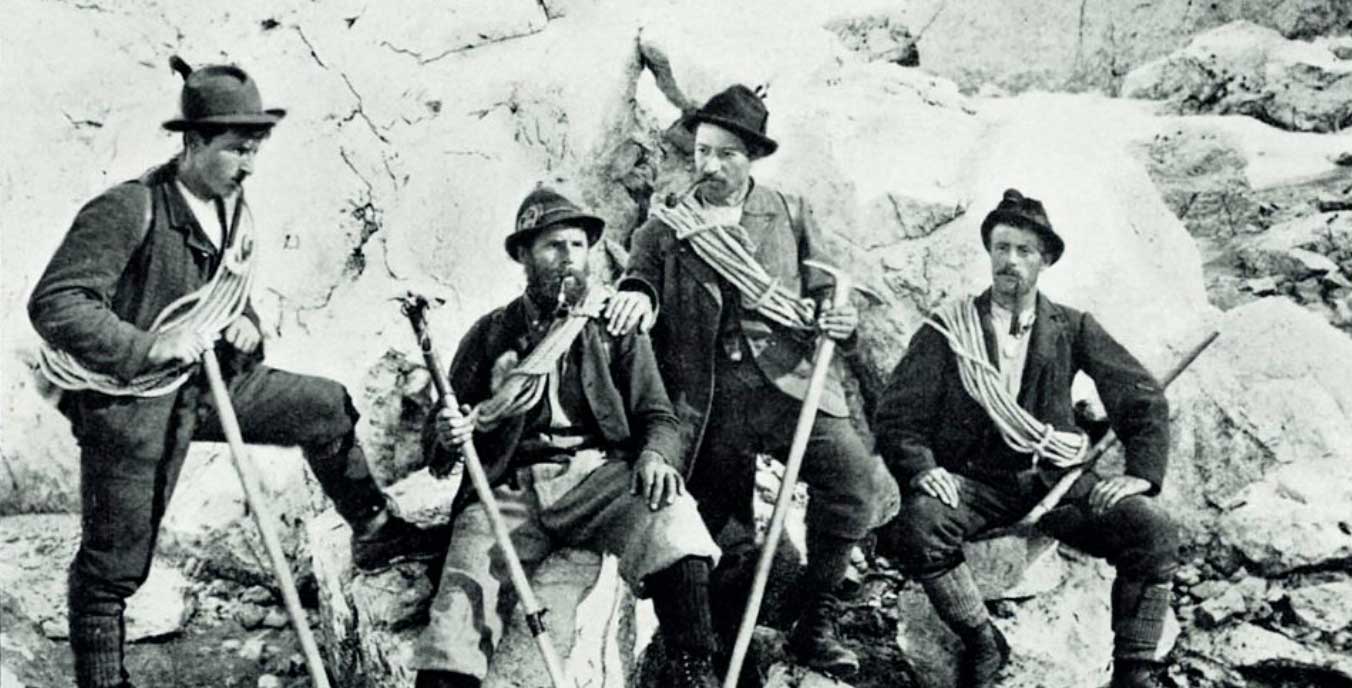

The birth of the Mountain Guides of San Martino, known as the “Aquile di San Martino” (Eagles of San Martino), dates back to 1881 when Michele Bettega became the first true Alpine Guide of the area, initiating a tradition that would mark the history of San Martino. Alongside Bettega, figures like Giuseppe Zecchini, Bortolo Zagonel, and Antonio Tavernaro emerged, forming the first core of the Eagles, the “famous quartet” as defined by Theodor Wundt. These pioneers forged a network of countless routes in the Pale di San Martino, emerging in a phase of mountaineering characterized by the search for difficulty, and standing out for their ability to conceive highly modern ascent lines. In total, the famous quartet opened a remarkable 125 new routes on the Pale di San Martino.

The heroic deeds of the famous quartet laid the foundation for a lasting tradition. Over time, the profession of Mountain Guide has evolved to adapt to the increasingly diverse requests of visitors, and today, with almost a century and a half of history behind them, the Guides of San Martino continue their mission, ensuring unforgettable experiences for their clients. The guides are equipped with meticulous technical preparation, certified by rigorous courses and exams, and many of them are also experts in mountain rescue, where they serve. Moreover, the Mountain Guides of San Martino are ready to accompany you along the exciting “Palaronda Ferrata with Guide” tours, ensuring you an experience in total safety.

On the Pale di San Martino, we find five alpine refuges among the most beautiful in the Dolomites, crucial resting points for high-altitude hikers. The first to be inaugurated was the Rosetta Hut in 1889, erected by the Trentino Mountaineers Society (SAT). The Pradidali Hut (1896) and the Treviso Hut (1897) followed, both built by the Dresden section of the German and Austrian Alpine Club (DÖAV), when the Trentine Dolomites were part of the Austro-Hungarian territory. The Mulaz Hut, built in 1907 by the Venice Section of the Italian Alpine Club (CAI), added another important stop to the range of refuges in the Pale di San Martino. Finally, the Velo della Madonna Hut completed the circle in 1980, also built by the Trentino Mountaineers Society (SAT).

© 2024 Palaronda | Rifugi nelle Pale di San Martino | P.IVA 01293320220 | Privacy & Cookie Policy | Made by ofprojects.com

This website uses cookies to improve your experience while you navigate through the website.

View the Cookie Policy View the Personal Data Policy

Google Fonts is a service used to display font styles operated by Google Ireland Limited and serves to integrate such content into its pages.

Place of processing: Ireland - Privacy Policy

Gravatar is an image visualisation service provided by Automattic Inc. that allows this Website to incorporate content of this kind on its pages.

Place of processing: United States - Privacy Policy

Google Analytics is a web analytics service provided by Google Ireland Limited ("Google"). Google uses the collected personal data to track and examine the usage of this website, compile reports on its activities, and share them with other Google services. Google may use your personal data to contextualize and personalize the ads of its advertising network. This integration of Google Analytics anonymizes your IP address. The data sent is collected for the purposes of personalizing the experience and statistical tracking. You can find more information on the "More information on Google's handling of personal information" page.

Place of processing: Ireland - Privacy Policy

Additional consents:

Azienda per il Turismo San Martino di Castrozza, Primiero e Vanoi

+39 0439 768867

booking@sanmartino.com

Azienda per il Turismo San Martino di Castrozza, Primiero e Vanoi

+39 0439 768867

booking@sanmartino.com

Tourist office San Martino di Castrozza, Primiero and Vanoi

+39 0439 768867

booking@sanmartino.com

Tourist office San Martino di Castrozza, Primiero and Vanoi

+39 0439 768867

booking@sanmartino.com

Browse through the sections of the page and discover interesting anecdotes and adventures that have made the history of the Pale di San Martino